""""

Foundations of Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning

Chapter 9 Figure 9.5

Author: Ulisses Braga-Neto

PCA example using the softt magnetic alloy dataset

"""

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler as ssc11 Homework 5

11.1 Description

Problems from the Book

9.8

11.11

Both problems are coding assignments, with starting code provided. Each is worth 40 points.

11.2 Problem 9.8

This assignment concerns the application of PCA to the soft magnetic alloy data set (See section A8.5).

11.2.1 (a)

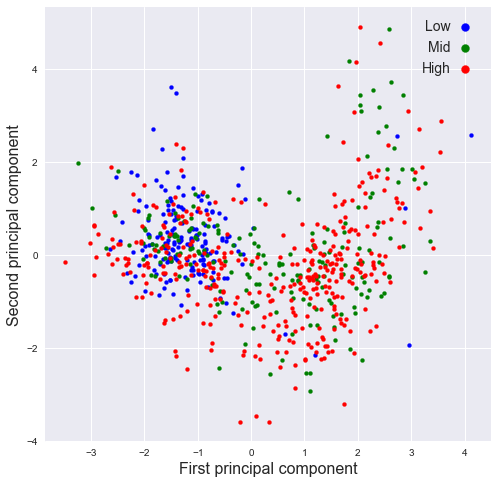

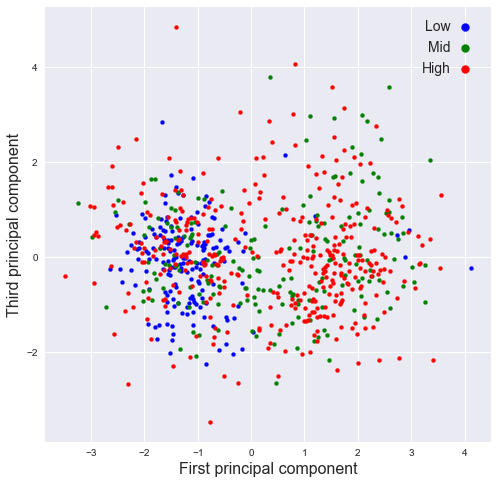

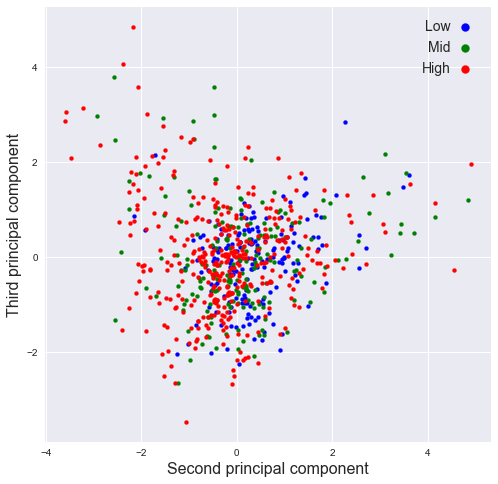

Reproduce the plots in Figure 9.5 by running c09_PCA.py

# Fix random state for reproducibility

np.random.seed(0)

SMA = pd.read_csv('data/Soft_Magnetic_Alloy_Dataset.csv')

fn0 = SMA.columns[0:26] # all feature names

fv0 = SMA.values[:,0:26] # all feature values

rs0 = SMA['Coercivity (A/m)'] # select response# pre-process the data

n_orig = fv0.shape[0] # original number of training points

p_orig = np.sum(fv0>0,axis=0)/n_orig # fraction of nonzero components for each feature

noMS = p_orig>0.05

fv1 = fv0[:,noMS] # drop features with less than 5% nonzero components

noNA = np.invert(np.isnan(rs0)) # find available response values

SMA_feat = fv1[noNA,:] # filtered feature values

SMA_fnam = fn0[noMS] # filtered feature names

SMA_resp = rs0[noNA] # filtered response values

n,d = SMA_feat.shape # filtered data dimensions

# add random perturbation to the features

sg = 2

SMA_feat_ns = SMA_feat + np.random.normal(0,sg,[n,d])

SMA_feat_ns = (SMA_feat_ns + abs(SMA_feat_ns))/2 # clamp values at zero

# standardize data

SMA_feat_std = ssc().fit_transform(SMA_feat_ns)

# compute PCA

pca = PCA()

pr = pca.fit_transform(SMA_feat_std)

# PCA plots

def plot_PCA(X,Y,resp,thrs,nam1,nam2):

Ihigh = resp>thrs[1]

Imid = (resp>thrs[0])&(resp<=thrs[1])

Ilow = resp<=thrs[0]

plt.xlabel(nam1+' principal component',fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel(nam2+' principal component',fontsize=16)

plt.scatter(X[Ilow],Y[Ilow],c='blue',s=16,marker='o',label='Low')

plt.scatter(X[Imid],Y[Imid],c='green',s=16,marker='o',label='Mid')

plt.scatter(X[Ihigh],Y[Ihigh],c='red',s=16,marker='o',label='High')

plt.xticks(size='medium')

plt.yticks(size='medium')

plt.legend(fontsize=14,facecolor='white',markerscale=2,markerfirst=False,handletextpad=0)

plt.show()

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(8,8))#,dpi=150)

plot_PCA(pr[:,0],pr[:,1],SMA_resp,[2,8],'First','Second')

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(8,8))#,dpi=150)

plot_PCA(pr[:,0],pr[:,2],SMA_resp,[2,8],'First','Third')

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(8,8))#,dpi=150)

plot_PCA(pr[:,1],pr[:,2],SMA_resp,[2,8],'Second','Third')

11.2.2 (b)

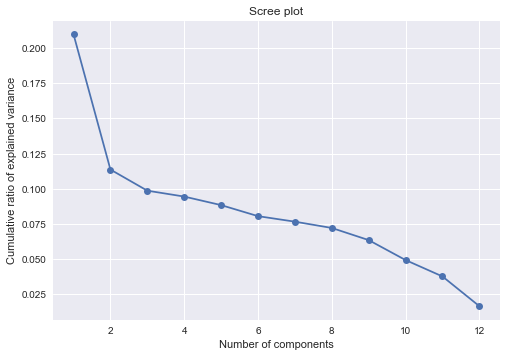

Plot the percentage of variance explained by each PC as a function of PC number. This is called the scree plot. Now plot the cumulative percentage of variance explained by the PCs as a function of PC number. How many PCs are needed to explain \(95\%\) of the variance.

Coding hint: use the attribute

explained_variance_ratio_and thecumsum()method.

n = len(pca.explained_variance_ratio_)

#plt.plot( np.arange(1, n+1) ,np.cumsum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_))

plt.plot( np.arange(1, n+1) ,pca.explained_variance_ratio_, "-o")

plt.xlabel("Number of components")

plt.ylabel("Cumulative ratio of explained variance")

plt.title("Scree plot")Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Scree plot')

np.cumsum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_)array([0.20991838, 0.32353309, 0.42210314, 0.51647789, 0.6047665 ,

0.68519162, 0.76168501, 0.83369708, 0.89706386, 0.94621316,

0.98369719, 1. ])np.where(np.cumsum(pca.explained_variance_ratio_) > 0.95)[0][0] + 111- 11 PCs are needed to explain 95% of the variance.

11.2.3 (c)

Print the loading matrix \(W\) (this is the matrix of eigenvectors, ordered by PC number from left to right). The absolute value of the coefficients indicate the relative importance of each original variable (row of \(W\)) in the corresponding PC (column of \(W\)). 1

#for i in range(0,n):

# print("Component", i+1,":",pca.components_[i].T)

wd = pd.DataFrame(pca.components_.T * np.sqrt(pca.explained_variance_ratio_), columns = ["PC{}".format(i+1) for i in range(0,n)])

wd.iloc[:,0:6]| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.217429 | -0.128414 | -0.000768 | -0.013032 | 0.025015 | -0.018742 |

| 1 | -0.231749 | 0.065983 | -0.014794 | -0.089591 | -0.010017 | 0.005178 |

| 2 | 0.032908 | 0.166780 | 0.078030 | 0.083952 | -0.009801 | -0.005831 |

| 3 | -0.093151 | -0.142560 | -0.098557 | 0.086218 | 0.086567 | -0.076516 |

| 4 | 0.198563 | 0.135102 | -0.001895 | -0.026140 | 0.032221 | 0.055660 |

| 5 | -0.026492 | 0.008521 | -0.036036 | 0.214858 | -0.108705 | -0.008577 |

| 6 | -0.017498 | -0.014458 | -0.162399 | -0.104232 | -0.065114 | 0.042457 |

| 7 | 0.052591 | -0.099443 | 0.151379 | -0.036285 | -0.161591 | -0.083255 |

| 8 | -0.157455 | 0.021118 | 0.011608 | 0.081410 | -0.001242 | 0.047744 |

| 9 | -0.041245 | 0.059526 | 0.063562 | -0.019442 | 0.142836 | -0.178096 |

| 10 | -0.010472 | -0.101413 | 0.114606 | 0.041513 | 0.123522 | 0.164500 |

| 11 | -0.171381 | -0.043990 | 0.121028 | -0.062770 | -0.033236 | 0.034567 |

wd.iloc[:,6:]| PC7 | PC8 | PC9 | PC10 | PC11 | PC12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.015495 | -0.005038 | 0.051062 | -0.046767 | -0.091825 | -0.070203 |

| 1 | -0.023988 | -0.035185 | -0.063599 | 0.058694 | -0.014704 | -0.085907 |

| 2 | -0.096659 | 0.160212 | -0.048367 | -0.038402 | -0.047184 | -0.010801 |

| 3 | -0.098246 | 0.066477 | -0.030437 | -0.034888 | 0.084873 | -0.020465 |

| 4 | 0.017248 | -0.016361 | 0.043242 | -0.027380 | 0.124907 | -0.045211 |

| 5 | 0.141188 | -0.028350 | -0.034109 | -0.016461 | 0.001849 | -0.032101 |

| 6 | 0.098092 | 0.169961 | 0.031244 | -0.005649 | -0.004468 | -0.001099 |

| 7 | -0.013892 | 0.063737 | 0.015561 | 0.073965 | 0.057188 | -0.012833 |

| 8 | -0.047099 | 0.012760 | 0.213021 | 0.033689 | -0.007880 | -0.009804 |

| 9 | 0.134329 | 0.040100 | 0.041069 | 0.012429 | -0.005979 | -0.004630 |

| 10 | 0.070125 | 0.069752 | -0.044561 | 0.062093 | 0.007589 | -0.009022 |

| 11 | 0.038157 | -0.002185 | 0.012125 | -0.170754 | 0.018848 | -0.004422 |

11.2.4 (d)

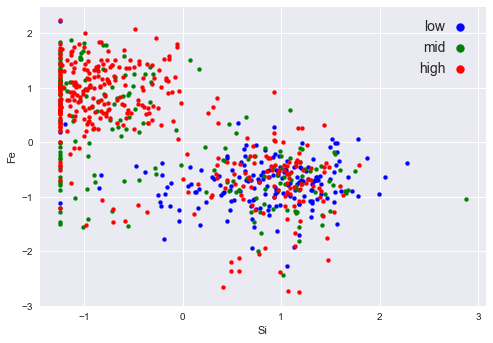

Identify which two features contribute the most to the discriminating first PC and plot the data using these top two features. What can you conclude about the effect of these two features on the coercivity? This is an application of PCA to feature selection.

most_id = np.abs(wd["PC1"]).argsort()[-2:].to_numpy()most_idarray([0, 1])thrs = [2, 8]

id_d = {

"high": SMA_resp>thrs[1],

"mid": (SMA_resp>thrs[0])&(SMA_resp<=thrs[1]),

"low": SMA_resp<=thrs[0]

}

cs = ["blue", "green", "red"]

for i, lb in enumerate(["low", "mid", "high"]):

plt.scatter(SMA_feat_std[id_d[lb], most_id[1]], SMA_feat_std[id_d[lb], most_id[0]],\

c= cs[i],s=16,marker='o',label=lb)

plt.legend(fontsize=14,facecolor='white',markerscale=2,markerfirst=False,handletextpad=0)

plt.xticks(size='medium');

plt.yticks(size='medium');

plt.xlabel(SMA_fnam[most_id[1]])

plt.ylabel(SMA_fnam[most_id[0]])Text(0, 0.5, 'Fe')

Relations 1. High: -1 ~ 2 in feature 1; -2 ~ 2 in feature 0 2. Mid: -1 ~ 0 in feature 1; -1 ~ 2 in feature 0 3. low: Approximately locates around -1 ~ 2 in feature 1, -3 ~ 1 in feature 0

There values are refferred to the normalized units.

11.3 Problem 11.11

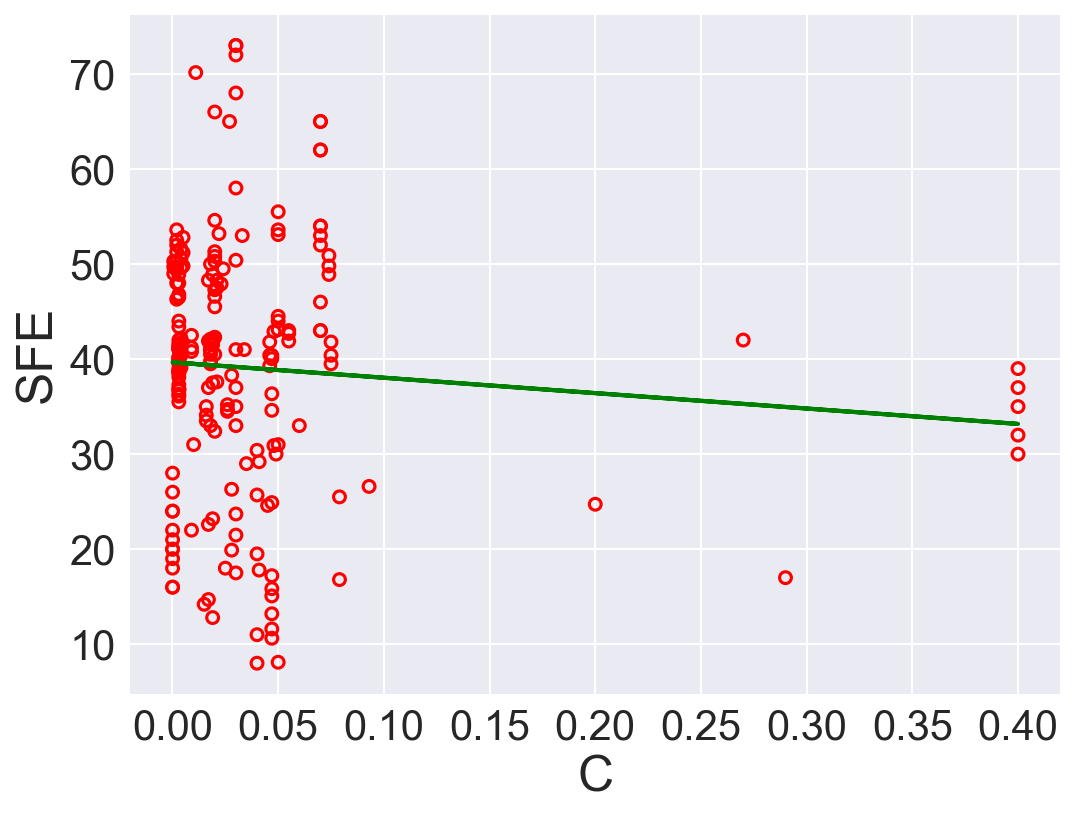

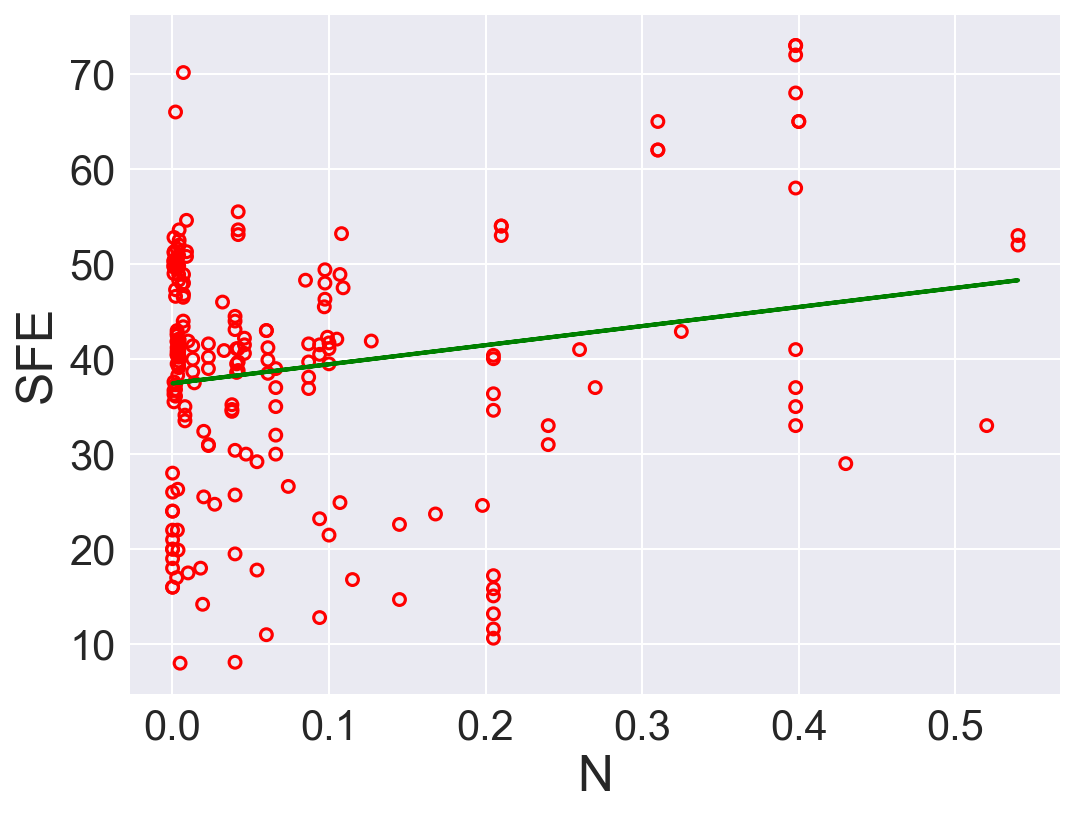

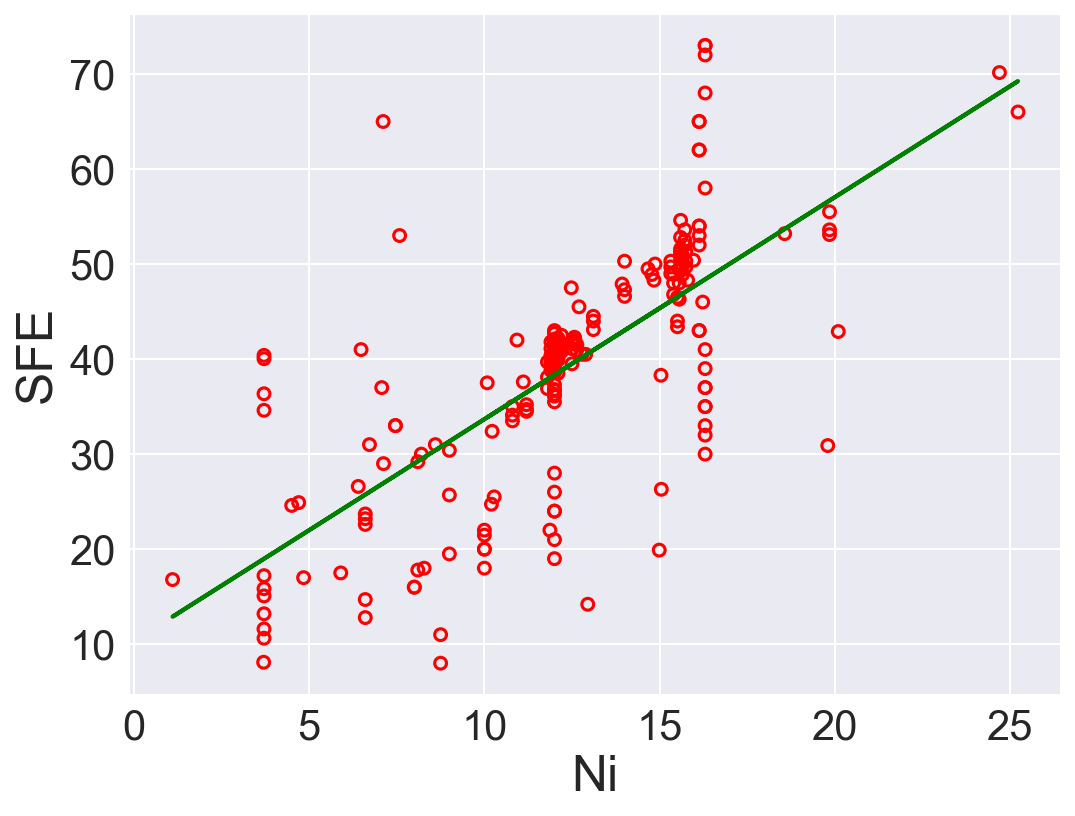

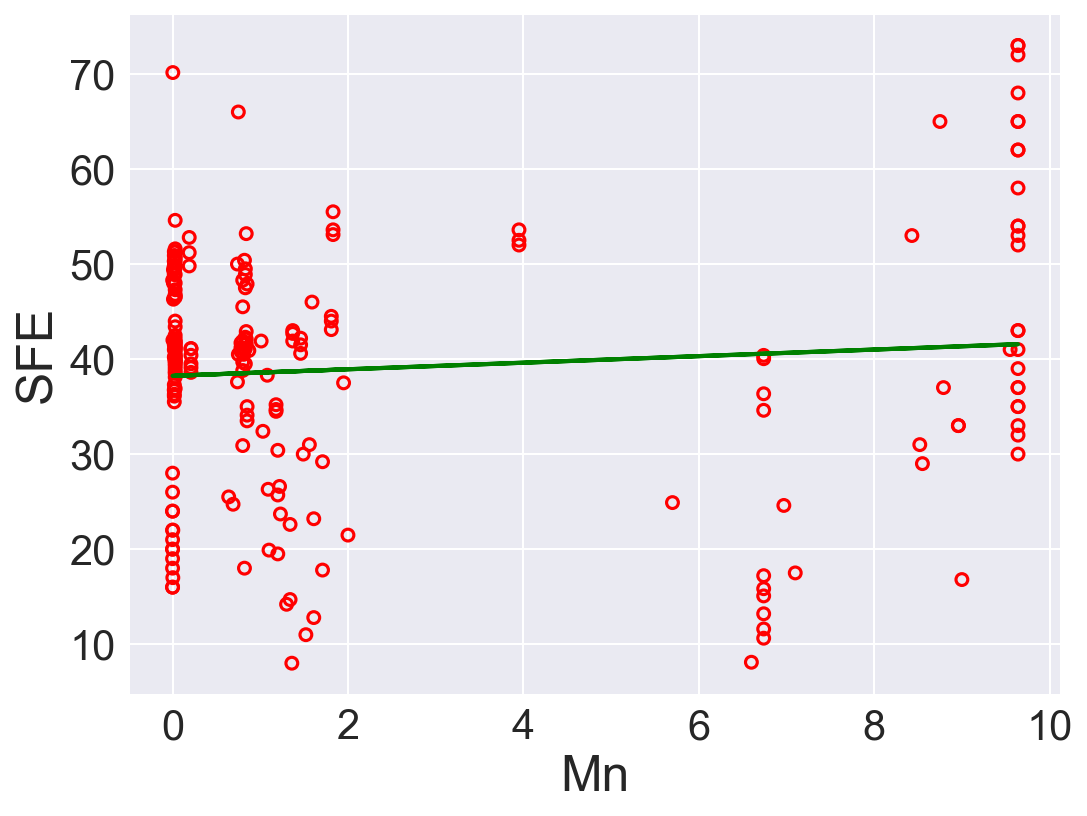

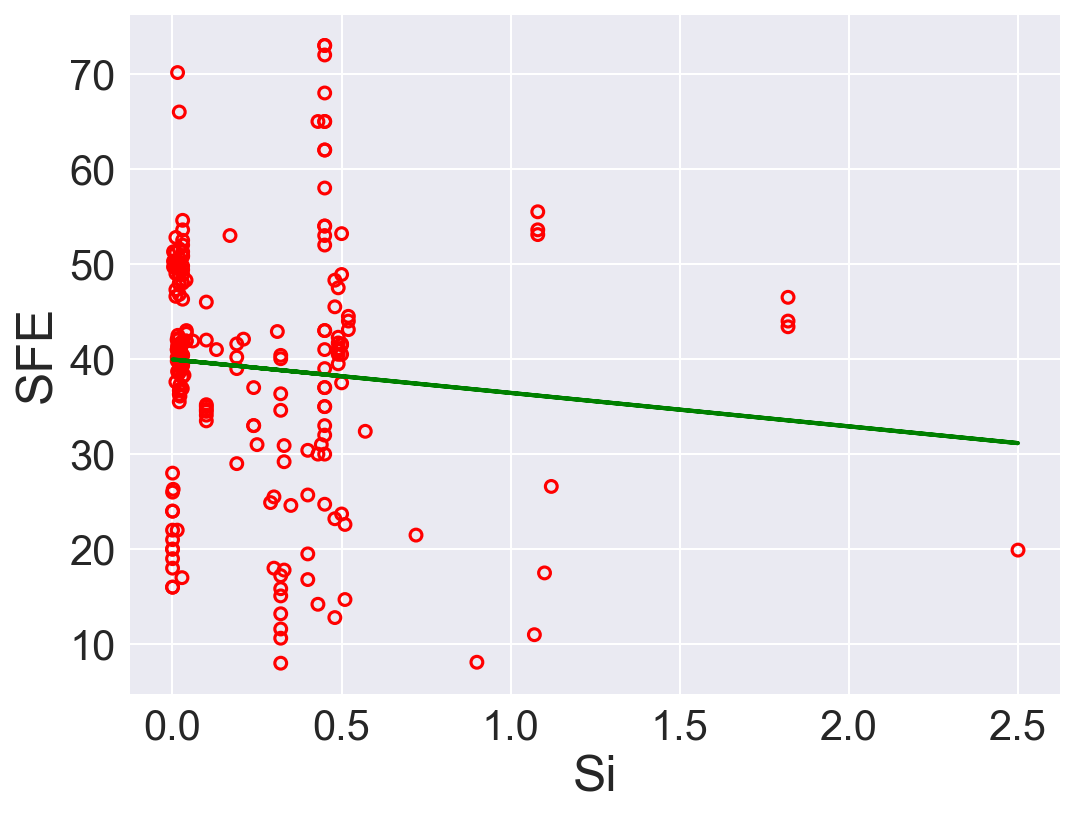

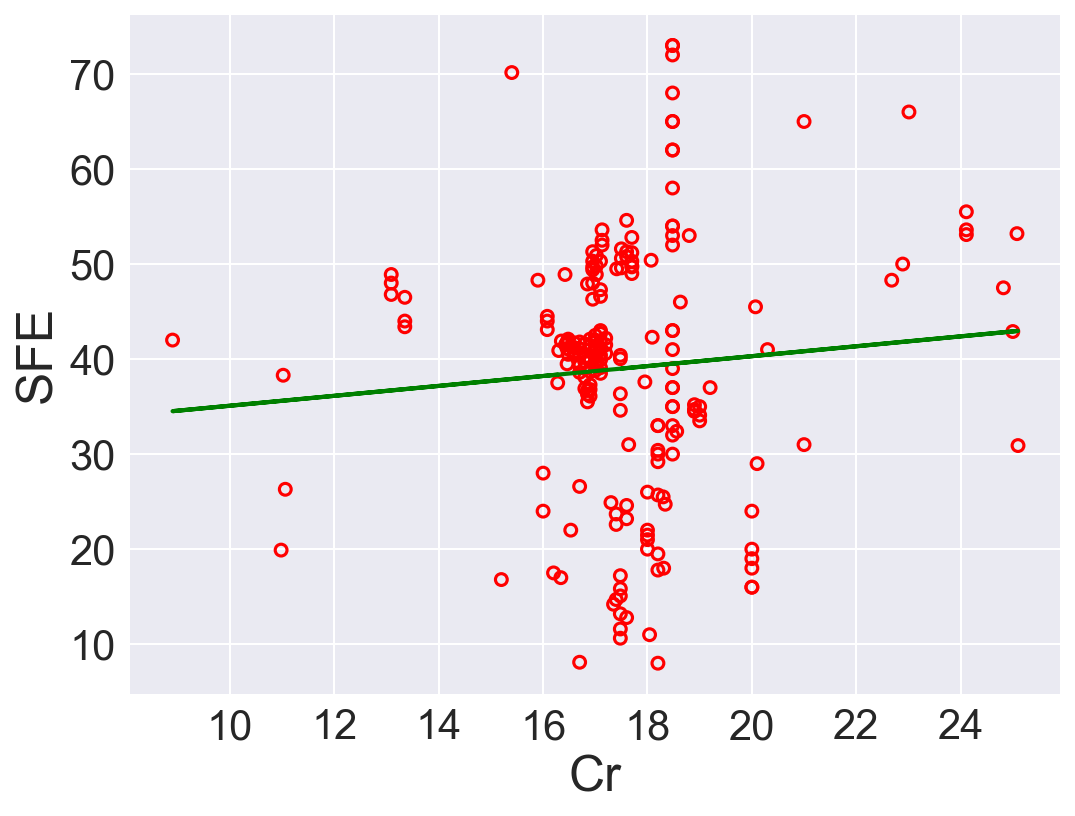

Apply linear regression to the stacking fault energy (SFE) data set.

11.3.1 (a)

Modify

c11_SFE.pyto fit a univariate linear regression model (with intercept) separately to each of the seven variables remaining after preprocessing (two of these were already done in Example 11.4. List the fitted coefficients, the normalized RSS, and the \(R^2\) statsitic for each model.Which one of the seven variables is the best predictor of SFE, according to \(R^2\)? Plot the SFE response against each of the seven variables, with regression lines superimposed. How do you interpret these results?

""""

Foundations of Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning

Chapter 11 Figure 11.3

Author: Ulisses Braga-Neto

Regression with a line example with stacking fault energy dataset

"""

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.base import clone

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import r2_score

plt.style.use('seaborn')MatplotlibDeprecationWarning: The seaborn styles shipped by Matplotlib are deprecated since 3.6, as they no longer correspond to the styles shipped by seaborn. However, they will remain available as 'seaborn-v0_8-<style>'. Alternatively, directly use the seaborn API instead.

plt.style.use('seaborn')def r2(model, x, y):

y_pred = model.predict(x)

return r2_score(y, y_pred)

def fitted_coef(model):

return model.coef_[0]

def fitted_int(model):

return model.intercept_

def normalized_RSS(model, xrr, yr):

y_pred = model.predict(xrr)

rss = np.sum(np.square(y_pred - yr)) / len(y_pred)

return rssSFE_orig = pd.read_table('data/Stacking_Fault_Energy_Dataset.txt')# pre-process the data

n_orig = SFE_orig.shape[0] # original number of rows

p_orig = np.sum(SFE_orig>0)/n_orig # fraction of nonzero entries for each column

SFE_colnames = SFE_orig.columns[p_orig>0.6]

SFE_col = SFE_orig[SFE_colnames] # throw out columns with fewer than 60% nonzero entries

m_col = np.prod(SFE_col,axis=1)

SFE = SFE_col.iloc[np.nonzero(m_col.to_numpy())] # throw out rows that contain any zero entriesyr = SFE['SFE']

model = LinearRegression()

res = {

"feature": [],

"slope": [],

"intercept": [],

"Norm RSS":[],

"R2": []

}

for feat in SFE.keys()[:-1].to_numpy():

xr = np.array(SFE[feat])

xrr = xr.reshape((-1,1)) # format xr for Numpy regression code

model.fit(xrr,yr)

# Performance

res["feature"].append(feat)

res["slope"].append(fitted_coef(model))

res["intercept"].append(fitted_int(model))

res["Norm RSS"].append(normalized_RSS(model, xrr, yr))

res["R2"].append(r2(model, xrr, yr))

# Plotting

fig=plt.figure(figsize=(8,6),dpi=150)

plt.xlabel(feat,size=24)

plt.ylabel('SFE',size=24)

plt.xticks(size=20)

plt.yticks(size=20)

plt.scatter(xr,yr,s=32,marker='o',facecolor='none',edgecolor='r',linewidth=1.5)

## Plotting regression model

plt.plot(xrr,model.predict(xrr),c='green',lw=2)

plt.show()

pd.DataFrame(res)| feature | slope | intercept | Norm RSS | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | C | -16.200376 | 39.658087 | 167.480699 | 0.006946 |

| 1 | N | 20.088487 | 37.447183 | 162.756200 | 0.034959 |

| 2 | Ni | 2.335338 | 10.324642 | 84.669120 | 0.497966 |

| 3 | Fe | -1.440431 | 134.100015 | 100.297936 | 0.405297 |

| 4 | Mn | 0.345602 | 38.236325 | 167.230592 | 0.008429 |

| 5 | Si | -3.520817 | 39.959897 | 167.129698 | 0.009027 |

| 6 | Cr | 0.521318 | 29.878868 | 167.428848 | 0.007254 |

According to \(R^2\), Ni is the best predictor that has positive linear relation between SFE. Also, Fe has high correlation coefficient. The rest of the features performs low correlation between SFE. As we can see in the linear regression plots.

11.3.2 (b)

Perform multivariate linear regression with a linear forward wrapper search (for 1 to 5 variables) using the \(R^2\) statistic as the search criterion. List the normalized RSS, the \(R^2\) statistic, and the adjusted \(R^2\) statistic for each model. Which would be the most predictive model according to adjusted \(R^2\)? How do you compare these results with those of item (a)?

Use the adjusted \(R^2\) formula:

\[R^{2}_{adj} = 1 - \frac{(1-R^2)(n-1)}{n-k-1}\]

Ref: Sequential forward search https://vitalflux.com/sequential-forward-selection-python-example/

def adr2(model, x, y):

r = r2(model,x,y)

N = x.shape[0]

p = x.shape[1]

return 1 - (1-r)*(N-1)/(N-p-1)

class SequentialForwardSearch():

def __init__(self, clf):

self.clf = clone(clf)

def search(self, xs, ys):

unchosen_ids = list(range(xs.shape[1]))

chosen_ids = []

self.scores = []

self.subset = []

self.r2 = []

self.rss = []

self.adr2 = []

while len(unchosen_ids) > 0:

scrs = [] #scores record

for i in unchosen_ids:

subset = chosen_ids + [i]

scrs.append( self._score(xs[:, subset], ys))

best_i = np.argmax(scrs) #best base

chosen_ids.append(unchosen_ids.pop(best_i)) # swap

# Rcord

self.scores.append(scrs[best_i])

# Performance

self.clf.fit(xs[:, chosen_ids], ys)

self.r2.append(r2(self.clf, xs[:, chosen_ids], ys))

self.rss.append(normalized_RSS(self.clf, xs[:, chosen_ids], ys))

self.adr2.append(adr2(self.clf, xs[:, chosen_ids], ys))

self.subset = chosen_ids

def _score(self, xs, ys):

self.clf.fit(xs, ys)

return r2(self.clf, xs, ys)

# data

xr = SFE.drop("SFE", axis=1).to_numpy()[:, 0:5]

yr = SFE['SFE']

# Search

sh = SequentialForwardSearch(LinearRegression())

sh.search(xr, yr)

ids_sh = sh.subset

## Performance

fts = [ str([res["feature"][j] for j in sh.subset[0:i+1]]) for i in range(0, len(sh.subset))] #features

pd.DataFrame({"Feature": fts, "R2": sh.r2, "Norm RSS": sh.rss, "Adjust R2": sh.adr2})| Feature | R2 | Norm RSS | Adjust R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ['Ni'] | 0.497966 | 84.669120 | 0.495564 |

| 1 | ['Ni', 'N'] | 0.553514 | 75.300860 | 0.549221 |

| 2 | ['Ni', 'N', 'C'] | 0.572860 | 72.038072 | 0.566670 |

| 3 | ['Ni', 'N', 'C', 'Fe'] | 0.579493 | 70.919455 | 0.571328 |

| 4 | ['Ni', 'N', 'C', 'Fe', 'Mn'] | 0.579832 | 70.862215 | 0.569584 |

If solely depends on \(R^2\), model with \(5\) is the best option. However, after adding regularization term with adjusted \(R^2\), model with \(4\) features is the best.

https://scentellegher.github.io/machine-learning/2020/01/27/pca-loadings-sklearn.html↩︎